This God Delusion stuff is not really much fun any more. I’ve written 48 posts on the first two chapters, which I realise was kind of obsessive. But my anger and frustration with the book, which fuelled all those posts (even though I hope that most of the time I managed to convert anger into analysis) has slowly turned to solid weariness. So, here’s the plan. I intend to write three posts on chapter 3: one on Aquinas, one on Anselm, and then one on the whole thing. And then I’ll do two posts per chapter for the remainder of the book: one of bullet-pointed gripes, one of more organised response. And then I’ll put it away and do something that doesn’t make me feel quite so gloomy (and add yet another item to my list of projects not quite carried through…)

Interim verdict, on The God Delusion, ch.2

Chapter 2 of The God Delusion convinced me that when Dawkins hears ‘theologian’, he thinks of two things: creationists, and Richard Swinburne. And that he revels in his ignorance of the religious tradition that he thinks is represented by such theologians.

Perhaps more importantly, the chapter simply does not engage with what ‘God’ means in some strands of religious belief that are not well represented by either creationists or Richard Swinburne. And, as I said much earlier, I do not mean that his account misses some nuances, or tramples on some nice decorative features of the understanding of ‘God’ in those strands. I mean that it misses them completely. And I happen to think that those strands of Christianity that Dawkins misses are at least as faithful to the historical Christian tradition as either creationism or Richard Swinburne.

Overall, the thing that strikes me most forcefully – and that has made working through this chapter so depressing at times – is the lack of real curiosity that Dawkins demonstrates. He really doesn’t care about understanding how any of the stuff he’s talking about works. He really doesn’t care what the people who disagree with him say. He’s just not interested. And, no, I don’t mean that he ought to like it more; I don’t mean that he ought to show it some kind of pious respect. But without rather more attention to whether his descriptions actually apply as universally as he thinks they do, it’s unsurprising that those descriptions fail to be particularly penetrating.

Oh well.

The Great Prayer Experiment

Ch.2: ‘The God Hypothesis’

Dawkins writes a lot about the ‘Great Prayer Experiment’ – a scientific study designed to test the efficacy of intercessory prayer. The experiment’s results did not show any efficacy. Dawkins, expreses a good deal of distaste about the whole thing. Fair enough.

He asks, however, whether, had the experiment instead proved the efficacy of intercessory prayer, ‘a single religious apologist would have dismissed it on the grounds that scientific research has no bearing on religious matters? Of course not.’ (90) Whereas the right answer is ‘Of course!’ I can think of all sorts of Christian thinkers who would have rejected it. There’s a debate in Christian theology on precisely this issue – a debate whose varying sides all argue on terms that make some sense within the Christian tradition, some of them just as fervently attached to the view of prayer assumed by the experiment as Dawkins’ targets, some at least as dismissive of it as Dawkins himself.

Dawkins does admit that there are some theologians who have rejected the whole basis of the experiment. He discusses Richard Swinburne again, as if he were a representative of Christian theology in general (he’s not; he’s really not!). And he notes that an American religious leader, Raymond Lawrence, was granted a ‘generous tranche of op-ed space in the New York Times‘ to reflect on the negative results of the intercessory prayer experiment. In the space of a few lines, he manages to insinuate (without evidence) that Lawrence is a hypocrite (he disowned the study only ‘after it failed’; ‘Would he have sung a different tune if the … study had succeeded…? Maybe not, but…’ – and then the quote I gave above, a paragraph later, which decisively erases the ‘maybe not’. Dawkins tells us nothing about the arguments Lawrence used – simply mining his article for one quoted story about a distasteful incident – leaving the reader to guess whether Lawrence approved or disapproved of the incident (he disapproved, by the way).

It’s hard to avoid, some of the time, the sense that Dawkins believes that anyone who disagrees with him on this sort of topic simply must be both stupid and dishonest. It’s even harder to avoid, a lot of the time, the sense that Dawkins is simply blithely unaware that there are long-standing, complex, varied, and robust ongoing arguments within mainstream religious traditions, about many of the topics he touches on – and that the criticisms he launches against religion are often rather facile echoes of criticisms made within the religious traditions themselves.

The tragic importance of theology

Writing the last two posts has made me think about the introduction to John Milbank’s The Word Made Strange (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997).

Today, theology is tragically too important. For all current talk of a theology that would reflect on practice, the truth is that we remain uncertain as to where today to locate true Christian practice. This would be, as it has always been, a repetition differently but authentically, of what has always been done. In his or her uncertainty as to where to find this, the theologian feels almost that the entire ecclesial task falls on his own head: in the meagre mode of reflective words, he must seek to imagine what a true practical repetition would be like. Or at least he must hope that his merely theoretical continuation of the tradition will open up a space for wider transformation.

Look closely: those words ‘tragically’, ‘uncertain’, ‘almost’, ‘meagre’ and ‘merely’ are important; far from marooning him on the shores of astonishing arrogance, they actually leave Milbank within sight of space I have been describing as the theologian’s: the place of the dim-witted sophisticate. (Okay, you really need to read the previous post, ‘On being dim-witted‘ if that sounds like a rather arbitrary insult.)

I can’t quite make Milbank’s words my own, however. Of course, there are days when the fragility, the cliff-edge precariousness, the mottled patchiness of ‘true Christian practice’ is all that I can see. And there are even more days when it is hard to see what on earth is supporting the true Christian practice that I have found (or that has found me): it is flourishing despite everything: it is flourishing despite the brackish cultural, conceptual, and ecclesiastical water that it is forced to drink.

But I take it that one of my tasks as a theologian – one, I may say, that I perform astonishingly badly – is, in the face of that deep uncertainty as to where true Christian practice is to be found, to look. And that is, perhaps, the note I miss in some of Milbank’s work: looking, in expectation of a gift.

On being dim-witted

In the previous post, I began answering Dawkins’ question about ‘Why any circles worthy of the name of sophisticated remain within the Church’. I tried to distinguish between remaining within a club for the like-minded and remaining within a tradition of moral and intellectual formation. In the former, what counts is the intellectual sophistication already achieved by members; in the latter, what matter is what is made possible – whether this is a conversation, an argument, worth participating in.

In the previous post, I began answering Dawkins’ question about ‘Why any circles worthy of the name of sophisticated remain within the Church’. I tried to distinguish between remaining within a club for the like-minded and remaining within a tradition of moral and intellectual formation. In the former, what counts is the intellectual sophistication already achieved by members; in the latter, what matter is what is made possible – whether this is a conversation, an argument, worth participating in.

In that answer, however, I accepted the terms of Dawkins’ question – and so treated myself as a ‘sophisticate’ whose relationship to those in the Church less sophisticated than myself needed justification. And although I meant what I said, I now want to dig a bit deeper, and to call the terms of that question into question themselves. I really don’t think they are the right way to think about why someone like me ‘remains’ in the Church.

I am going to travel towards my point in rather rambling fashion, beginning from a point I discussed a little while ago. I talked about Christianity being in some respects something like a ‘worldview’. (That description also breaks down in important ways, as I said in that post, but it will do for now.) I talked about the ways in which a worldview might appropriately be judged, according to its coherence, resilience, and habitability – terms I explained a little more fully in that post (though at this abstract level of discussion they’re not really fully defined criteria, but gestures in the direction of whatever analogous criteria will make proper intrasystematic sense within a given worldview). To ask about the rationality of a worldview is to ask these kinds of questions.

If, however, we’re talking about the processes by which such a ‘worldview’ takes hold of someone, or lets them go, we might need another category. When someone slips away from Christian faith, for example, it seldom happens by means of one knockdown argument. Often it seems to involve a slow leeching away of that faith’s plausibility. ‘Plausibility’, here, is closely connected to the ‘habitability’ of that faith, – but now that habitability as compared to the habitability of other worldviews that are available to the person in question – other worldviews that he or she also partially inhabits. And this comparative habitability has to do with the ease, the facility, with which Christian ways of making sense come naturally and forcefully to hand as compared to some other way of making sense.

The leeching away of plausibility is the process by which this worldview shifts from being the water in which one swims to being a game that one plays, and from being a game that one plays to being a set of artificial moves that no longer form a whole – moves that sit oddly within some other context that has itself now usurped the aura of plausibility. In the other direction, a ‘worldview’ that ‘takes on the aura of plausibility’ will move from being a set of disruptive ideas, to being a game worth playing, to becoming invisible: the tacit rules that structure how one sees and moves.

Now, I live in a world in which Christian faith is counter-cultural (even though, in many contexts, ‘faithiness‘ is not). That is, I live in a world where what I am calling the Christian worldview tends only to flourish where people take pains over that flourishing, and where there is a background alternative worldview – in many ways inimical to Christianity – ready to take up the slack should faith weaken. Put it this way: I live in a world in which it is quite easy to stop participating in the eucharist, or reading the Bible, but rather more difficult to avoid shopping in supermarkets and watching Hollywood films. The disciplined practices that tend to sustain the Christian worldview are easier to avoid than the disciplined practices that tend to sustain one alternative.

Now: with that machinery in place, I can begin to approach my point. I spend a lot of my time skirting the edges of unbelief. For me, what I have been calling the ‘plausibility’ of Christianity ebbs and flows – and the sea of faith is not at high tide right now, and hasn’t been for a long time. In part, that has something to do with specific questions and problems that I have – specific matters of this worldview’s coherence and resilience. But only in part – and only in a pretty small part, if I’m honest. It is more a case of what I have been describing: the slow leeching away of plausibility. I spend quite a lot of my time at the ‘game that I play’ level of plausibility; on bad days I’m at the ‘set of artificial moves’ level. Only some of the time am I swimming in water that is truly transparent.

Now, an atheist observer might think that I simply lack courage to take the final step away from belief to unbelief – that I am held back by loyalty, by inertia, by fear, by cowardice. Come on, he might say, admit it: admit that faith has gone, and learn to celebrate that fact. (To be frank, though, it’s not so much Dawkins whose voice I hear at this point as Nietzsche, speaking in The Gay Science of the ‘freedom of the will [by which] the spirit would take leave of all faith and every wish for certainty, being practiced in maintaining himself on insubstantial ropes and possibilities and dancing even near abysses.)

That, however, is to beg the question. It is a description of my state (and a proposal of a solution) that only makes sense in terms of the atheist’s worldview – not in the Christian worldview. I cannot accept it as a reason for moving from the latter to the former without already having decided to move.

Instead, working still with the descriptions that make sense within Christianity (whether they come naturally to me, today, or seem artificial) I diagnose my plight differently. What do I expect, my faith tells me, in a life that sits so lightly to the disciplines that sustain faith’s plausibility? What do I expect in a life where the strings of prayer, of worship, of any form of devotion, are so very frayed? Any worldview (the atheist’s included) is sustained by disciplines of thought and practice; what do I expect from lack of discipline if not the leeching away of faith’s plausibility? Under such a description, the leeching away of plausibility does not tell me something uncomfortable about the Christian worldview, it tells me something uncomfortable about myself.

(Let me stress that I do not mean to suggest that doubt is sin. But some forms of doubt – if that is in any case a good word for this plausibility deficit – can be a symptom not of serious questioning and exploration, but of sloth: of having lazily allowed the fabric of faith to wear so thin that it frays.)

I do not mean this to be an ever-so-humble admission designed to place me in a good light, even though I know that there is no way of avoiding this being self-serving, no way of avoiding this itself being an appeal to you to marvel at my moral seriousness and clear-eyed self-scrutiny. I’m not talking about anything very interesting – nothing that involves any agonising or moral heroism or struggles at my personal Jabbok Ford. I’m talking about forgetfulness, about being bad at forming good habits, about boredom, about being easily distracted, about having will-power as strong as well-cooked spaghetti. It’s not going to make a good movie, believe me.

‘Sophisticated’ I may be, but I am not one of those in whom the Christian ‘worldview’ has remained second nature. I am not one of those who inhabits and embodies it deeply. And I am therefore – because these things do go together – not someone anyone should look to for the marks of those who do know this worldview more deeply: real discrimination, real judgment, real graciousness, facility and penetration.

I may be a good reader of texts on choreography, but you really wouldn’t want to see me dance.

So, ‘sophisticated’ I may be, but I think I count as one of Christianity’s ‘dim-witted’: those who labour to make out what others simply see; those who have to work at what for others has become second nature; those who know how to do this stuff in theory but fall over when doing it in practice. And I don’t think I can get away with some facile intellectual/practical distinction here, as if I’m good at the head stuff but bad at the body stuff. The facility, the grace, the judgment that those who more deeply inhabit the Christian worldview have – it’s a matter of what they see as much as a matter of what they do.

The real ‘sophisticates’ of Christianity are those who show Christian sophia: Christian wisdom. My sophistication is all second hand. I’m a a repairer of borrowed clothes

So, why don’t I leave the Church? Because these are my people: these are the anchors of my faith. Without them any version of Christianity that I tried to weave would be all thread and no fabric.

On being sophisticated

Ch.2: ‘The God Hypothesis’

Why any circles worthy of the name of sophisticated remain within the Church is a mystery at least as deep as those that theologians enjoy. (84)

Dawkins is, I think, genuinely puzzled as to why people who show all the normal signs of being intelligent, thoughtful, reasonable members of society persist in associating themselves with the Church. Partly, I take it, this is simply another way of expressing his fundamental incredulity: How could anyone believe anything so patently vacuous, so ill-grounded and confused, so improbable and easily refuted, as the existence of God?

The sentence I have quoted comes after Dawkins’ discussion of the silliness beyond parody of Catholic beatification processes – a process that he assumes must be an embarrassment to ‘more sophisticated circles within the Church’. Then comes the line I started with: in context, a throwaway jibe. But although it is a throwaway line, a taunt rather than an argument, it echoes a more serious question that I have heard Dawkins ask, in his curiously engaging interview with Richard Harries, then Bishop of Oxford (pictured). Dawkins describes Harries as liberal, then asks whether it might not be the conservatives who are truer to the real nature of religion; Harries comes back (not quite answering) with an explanation of why he thinks the liberal direction he has taken makes sense, prompting Dawkins to say, ‘This of course is all music to my ears, but I’m kind of left wondering why you stick with Christianity at all.’ There’s a comment on the page I’ve linked to which puts it more pithily: ‘Imagine how awful it must be for [Harries] to look out over a world full of people who, in a sense, share his faith, but who inevitably come across as thundering morons’ (Comment by ImagineAZ).

The sentence I have quoted comes after Dawkins’ discussion of the silliness beyond parody of Catholic beatification processes – a process that he assumes must be an embarrassment to ‘more sophisticated circles within the Church’. Then comes the line I started with: in context, a throwaway jibe. But although it is a throwaway line, a taunt rather than an argument, it echoes a more serious question that I have heard Dawkins ask, in his curiously engaging interview with Richard Harries, then Bishop of Oxford (pictured). Dawkins describes Harries as liberal, then asks whether it might not be the conservatives who are truer to the real nature of religion; Harries comes back (not quite answering) with an explanation of why he thinks the liberal direction he has taken makes sense, prompting Dawkins to say, ‘This of course is all music to my ears, but I’m kind of left wondering why you stick with Christianity at all.’ There’s a comment on the page I’ve linked to which puts it more pithily: ‘Imagine how awful it must be for [Harries] to look out over a world full of people who, in a sense, share his faith, but who inevitably come across as thundering morons’ (Comment by ImagineAZ).

I have two contrasting answers to this question. In this post, I’ll concentrate on the one that assumes that I count as one of the ‘sophisticated’ – because I do things like writing this blog. In a later post, I’ll call that idea into question, and suggest a different answer, but for now I’ll assume that I have the credentials to get into the sophisticated club. I can, after all, give Brains-Trust, ‘it depends what you mean by…’ answers at the drop of a hat.

To the question why I, as a soi-disant sophisticate, cast my lot in with the lumpenchristians, I might simply say, ‘Because I believe the Christian faith to be true.’ But remember, I’m the kind of person who says ‘It depends what you mean by…’ a lot, and Dawkins’ question is really about whether the resemblance between my beliefs and those of the broad mass of Christianity is strong enough to justify my staying with them. My real answer begins the moment I say, ‘No, no – Christianity is not a community of the like-minded, held together simply by the resemblance of our opinions. It’s something different: it’s a people. And one of the things that I believe is that I am called to be a member of that people – that I am made a member of that people.’

Let me spell that out a little more.

- When I look at the church, I don’t say, ‘These people think as I do’; I say, ‘They are my people.’ I belong to this people. They’re not my choice (no, really, they’re not): they’re given to me (and I to them, poor souls).

- But, in part, what I am given I am given qua sophisticate: I am given something that speaks to me and captivates me as an intellectual.

- When I look at the church, I don’t primarily see a body of beliefs – I see (amongst other things) the preservation of a set of practices and stories, habits and relationships, that make something possible. All living and thinking is shaped by the spaces in which it takes place – and these practices and stories, habits and relationships create a certain kind of space for thinking and living well.

- When I look at the church, I find that the practices and stories, habits and relationships it provides create a home in which a possibility of thinking well is preserved. They create a vocabulary, a grammar which enable me to pose and pursue questions – to go on asking, and thinking, and questioning, and revising, and discovering, and changing, and developing. I find here the possibility of being confronted with, and helped to do some justice to, aspects of the ways things are to which I suspect I would otherwise be numb.

- When I look at the church, I find that the practices and stories, habits and relationships it provides create a home in which a possibility of living well is preserved. That is, they create a vocabulary, a grammar – a set of building blocks which allow for certain kinds of pattern of life. And I am captivated by the possibilities for such patterned life that I find here.

- When I look at the church, I find that the practices and stories, habits and relationships it provides create a home in which a possibility of ‘living well’ and ‘thinking well’ is preserved, even though in that same church there is much bad thinking and bad living (including much of my own). But those possibilities still captivate me and call to me, and the people amongst whom they are preserved and betrayed, preserved and betrayed, preserved and betrayed, are my people: I stay because despite everything they keep the possibilities alive, and I stay to help keep those possibilities alive.

I’m not making comparative statements. That is, I’m not here saying that parallels or equivalents to the things I find here can’t be found elsewhere. But I am saying that I do find them here – and that the water is deep enough for a ‘sophisticated believer’ to swim in. Or, to change the metaphor: the church is not prose to the sophisticate’s poetry: it is rhyme-scheme and metre.

The only problem is, I’m not sure that calling myself a ‘sophisticated believer’ will do. But that’s another story…

Why bother?

Anyone who has ended up reading this blog because of my posts on Rowan Williams and sharia should probably know that with the next post I will be returning, like the proverbial dog, to my long-running series on Richard Dawkins’ book, The God Delusion.

Anyone who has ended up reading this blog because of my posts on Rowan Williams and sharia should probably know that with the next post I will be returning, like the proverbial dog, to my long-running series on Richard Dawkins’ book, The God Delusion.

To answer the obvious question: No, I don’t think the book inherently deserves this level of attention.

I do, however, think that my colleagues’, students’, and fellow-citizens’ fascination with the book makes this worth doing. And my hunch is that even if some of his specific arguments are idiosyncratic, when it comes to his basic, unquestioned assumptions about what religion is, and what ‘God’ means, he is speaking for many (including not a few within the Christian church).

So, think of these posts as my attempt to jump through a portal that Dawkins has opened into the errorsphere: that pulsating network of distorted concepts that powers our surface world. (This is the bit of the blog that will most need the help of Industrial Light and Magic once the film rights are sold.)

I should also, by the way, say that I plan to leaven this some time soon with (a) a return to the Gospel of Mark, and (b) a detailed reading of something more interesting. Any suggestions for the latter – something that it would be fun and productive to read slowly online – are welcome. Anyway, on with the show.

Williams and Sharia: Coda

I’m not planning on writing any more about Rowan Williams – at least, not any time soon. But I did want to point to a few other good discussions of the episode available elsewhere on the web.

What is Enlightenment? More on Williams and Sharia

The account I have already given of Williams’ speech on Civil and Religious Law in England was, despite it’s neuron-numbing length, seriously incomplete. Facing one set of Williams’ critics, I concentrated on demonstrating that Williams had not ridden roughshod over everything that secularists and advocates of universal human rights hold dear. I described his lectures as a ‘serious and impassioned defence of ‘Enlightenment values’. I stand by that – but it does need to be put in context.

I can best approach that context by quoting famous words written by one of Rowan Williams’ friends:

Once, there was no ‘secular’. And the secular was not latent, waiting to fill more space with the steam of the ‘purely human’, when the pressure of the sacred was relaxed…. The secular as a domain had to be instituted or imagined, both in theory and practice. – John Milbank, Theology and Social Theory: Beyond Secular Theology, 2nd edn (Oxford: Blackwell, 2006 [1990]), 9.

Williams shares something of the same understanding: that the ideas and practices that underpin the ‘secular’ – the ideas and practices from which we have woven a state capable of hosting multiple religious communities, and of subjecting all of them to a common framework of rights – were not miraculously chiselled on granite tablets and dropped onto the toes of a passing republican or philosophe at the start of the eighteenth century. Those ideas and practices have a history.

Like Milbank, Williams does not think that history is a story of the inevitable emergence of secularity, waiting only upon the crumbling of the sacred, as if secularity is the natural state of humankind. Rather, the history of secularity’s emergence is contingent: one can ask, Where did this come from? Why here? Why now? And, like Milbank, Williams thinks that the story one needs to tell in order to understand this contingent emergence is a thoroughly religious, theological story. The Enlightenment may emerge as a rejection of all sorts of aspects of fractious Christianity – but it is a rejection that was enacted by hands holding weapons pulled from Christian trees. (If you want a philosophically robust account of the kind of dynamics involved in this process, I’d recommend Peter Ochs, Peirce, Pragmatism, and the Logic of Scripture.)

As Williams puts it, the invention of secularity required (amongst other things)

a certain valuation of the human as such and a conviction that the human subject is always endowed with some degree of freedom over against any and every actual system of human social life; both of these things are historically rooted in Christian theology, even when they have acquired a life of their own in isolation from that theology. It never does any harm to be reminded that without certain themes consistently and strongly emphasised by the ‘Abrahamic’ faiths, themes to do with the unconditional possibility for every human subject to live in conscious relation with God and in free and constructive collaboration with others, there is no guarantee that a ‘universalist’ account of human dignity would ever have seemed plausible or even emerged with clarity. Slave societies and assumptions about innate racial superiority are as widespread a feature as any in human history (and they have persistently infected even Abrahamic communities, which is perhaps why the Enlightenment was a necessary wake-up call to religion…).

Why does this matter? Because if it is true, then any picture of a straightforward opposition between religion and the secular is a drastic oversimplification. And that means that any cry that simply says, ‘You can’t do this religious stuff; we’re secular!’ is talking as much nonsense as the cry that says, ‘You can’t do this secular stuff; we’re a Christian nation!’

To understand the history of secularity’s emergence, Williams thinks, is to see the sheer ungrounded assertion involved any simple story which sees ‘unqualified secular monopoly’ as the natural end-point of the Enlightenment, the only consistent interpretation and application of ‘Enlightenment’ principles. (And that goes for all those who tell this story with boos, as well as those who tell it with cheers.) That story-line is not built in to the very idea of the secular; far from it. And so Williams can say that to defend

an unqualified secular legal monopoly in terms of the need for a universalist doctrine of human right or dignity is to misunderstand the circumstances in which that doctrine emerged, and [to understand] that the essential liberating (and religiously informed) vision it represents is not imperilled by a loosening of the monopolistic framework.

(That sentence needs reading carefully: Williams is not denying the need for a ‘universalist doctrine of human right or dignity’, but rather denying that such a doctrine is secular-and-so-inherently-opposed-to-religion, and so denying that a militant defence of such a doctrine is at the same time a defence of ‘unqualified secular monopoly’.)

Further

what I have called legal universalism, when divorced from a serious theoretical (and, I would argue, religious) underpinning, can turn into a positivism as sterile as any other variety.

The narrative that Williams is offering as an alternative to the simplistic secularity-versus-religion narrative can, if taken seriously, enable one to name a form of oppression that would otherwise slip through our conceptual nets: the oppression of a sterile positivism which denies all possibility of – at very least – conscientious objection.

Let me explain that last comment a bit further. In the famous radio interview, Williams said:

a lot of what’s written suggests that the ideal situation is one in which there is one law and only one law for everybody; now that principle that there’s one law for everybody is an important pillar of our social identity as a Western liberal democracy, but I think it’s a misunderstanding to suppose that that means people don’t have other affiliations, other loyalties which shape and dictate how they behave in society and that the law needs to take some account of that. An approach to law which simply said: “There is one law for everybody and that is all there is to be said.” I think that’s a bit of a danger.

I read several comments in the aftermath saying something like, ‘That there is one law for everybody, and that that is all there is to be said, is and should continue to be the essence of our legal system’. But the language of ‘conscientious objection’ (that Williams uses in that article) points us to at least one example that is not so easy to ridicule. Suppose conscription were introduced again in some future state of war. Should that law make any provision for conscientious objection by pacifists of various kinds (including, but not limited to, religious groups like Quakers)? That is, should the law allow certain kinds of exception, based on the ‘consciences’ of the people in question? Or should it simply say, ‘No, there is one law for everybody and that is all there is to be said. Pick up your gun, soldier!’?

However, the point I want to focus on here is that at the heart of Williams’ strategy for advocating this as a valid interpretation and fulfilment of what is best in the Enlightenment project is an interpretation of the emergence of that Enlightenment – an interpretation that sees that it is made possible by certain crucial theological developments. Indeed, Williams is going further: he thinks that what is properly central to the Enlightenment, properly at the heart of secularity, is an ‘Abrahamic’ insight: ‘a commitment to human dignity as such‘. And so Williams is a defender of this core of the Enlightenment heritage because he is a Christian, and he is advocating ‘interactive pluralism’ as an interpretation of the Enlightenment heritage because in defending these aspects of the Enlightenment heritage he is doing his job: he is asking how the implications of the Christian Gospel can be worked out in the world. Far from proposing a solution that ignores the Christian heritage of this country, he is taking that heritage far more seriously than those who think it sets up some kind of magic magnetism that repels any negotiation with, or recognition of, Muslim consciences.

(Just as an aside, it’s worth noticing an interesting symmetry in Williams’ argument. It is only by understanding the emergence of ‘Enlightenment values’ – the tradition of theological and moral inquiry from which they emerge – that one can understand what are appropriate and inappropriate ways of defending them. It is only by telling the story so far that one can make judgments about what is central and what is peripheral, and so know how to go on in difficult circumstances. And just so with sharia: Williams suggests that it is only by a nuanced understanding of the contexts of sharia’s emergence and deployment that one can make appropriate judgments about what is central to it and what peripheral, and so know how to defend it in difficult circumstances.)

Of course Williams does not think that only Christians (or Jews or Muslims) can be truly committed to the Enlightenment project. Of course he does not think that no one else really cares about human dignity as such. Of course he does not think that Christianity (or Islam or Judaism) has a great record when it comes to the actual upholding of this idea. Nevertheless, he believes it is an idea that grew in theological soil – and so an idea that might still stand to be illuminated by theological exploration.

Of course, this particular lecture (not delivered to a particularly theologically aware audience) leaves the details of Williams theological case rather sketchy. I’m looking forward to finding out more, because it seems to me that there’s an interesting distance between Williams and Milbank emerging: on the face of it, Williams seems to be advocating a more positive account of the theological roots (and routes) of the Enlightenment, and of liberalism, than I’ve seen from Milbank (and yet doing it in terms which at heart are not obviously inimical to Radical Orthodoxy). The most pregnant hint in the lecture is Williams’ comment about ‘universal law and universal right’ being ‘a way of recognising what is least fathomable and controllable in the human subject’ – i.e., a way of recognising the ways in which human beings exceed any of the particular contexts in which their identities are formed. (I’m reminded of Susannah Ticciati’s Job and the Disruption of Identity, which would, I think, say that this is the realm of the ‘for naught’ and ‘for God’s sake’ of human identity.) As Williams says,

theology still waits for us around the corner of these debates, however hard our culture may try to keep it out. And, as you can imagine, I am not going to complain about that.

Me neither.

Shameless Self-promotion

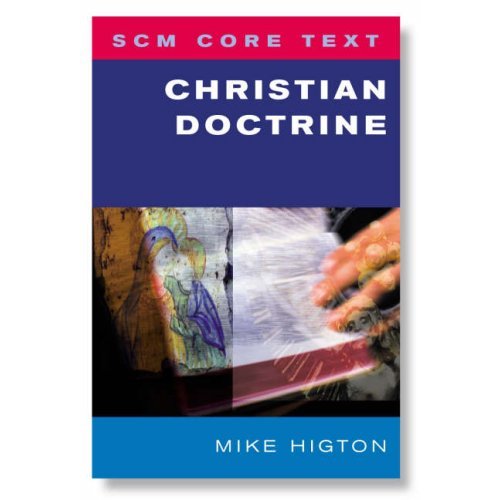

Amazon having sorted itself out (it had some name-spelling and book-description issues), I can now link to my latest:

Mike Higton, Christian Doctrine, SCM Core Text (London: SCM, 2008), 403pp

“The SCM Core Text: Christian Doctrine offers an up-to-date, accessible introduction to one of the core subjects of theology. Written for second and third-year university students, it shows that Christian Doctrine is not a series of impossible claims to be clung to with blind faith. Mike Higton argues that it is, rather, a set of claims that emerge in the midst of Christian life, as Christian communities try to make enough sense of their lives and of their world to allow them to carry on.

“Christian communities have made sense of their own life, and the life of the wider world in which they are set, as life created by God to share in God’s own life. They have seen themselves and their world as laid hold of by God’s life in Jesus of Nazareth, and as having the Spirit of God’s own life actively at work within them. This book explores these and other central Christian doctrines, and in each case, shows how the doctrine makes sense, and how it is woven into Christian life.

“It will help readers to see what sense it might make to say the things that Christian doctrine says, and how that doctrine might affect the way that one looks at everything: the natural world, gossip, culture, speaking in tongues, politics, dieting, human freedom, love, High Noon, justice, computers, racism, the novels of Jane Austen, parenthood, death and fashion.”

Recent Comments