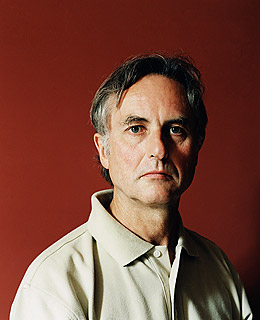

In the previous post, I began answering Dawkins’ question about ‘Why any circles worthy of the name of sophisticated remain within the Church’. I tried to distinguish between remaining within a club for the like-minded and remaining within a tradition of moral and intellectual formation. In the former, what counts is the intellectual sophistication already achieved by members; in the latter, what matter is what is made possible – whether this is a conversation, an argument, worth participating in.

In the previous post, I began answering Dawkins’ question about ‘Why any circles worthy of the name of sophisticated remain within the Church’. I tried to distinguish between remaining within a club for the like-minded and remaining within a tradition of moral and intellectual formation. In the former, what counts is the intellectual sophistication already achieved by members; in the latter, what matter is what is made possible – whether this is a conversation, an argument, worth participating in.

In that answer, however, I accepted the terms of Dawkins’ question – and so treated myself as a ‘sophisticate’ whose relationship to those in the Church less sophisticated than myself needed justification. And although I meant what I said, I now want to dig a bit deeper, and to call the terms of that question into question themselves. I really don’t think they are the right way to think about why someone like me ‘remains’ in the Church.

I am going to travel towards my point in rather rambling fashion, beginning from a point I discussed a little while ago. I talked about Christianity being in some respects something like a ‘worldview’. (That description also breaks down in important ways, as I said in that post, but it will do for now.) I talked about the ways in which a worldview might appropriately be judged, according to its coherence, resilience, and habitability – terms I explained a little more fully in that post (though at this abstract level of discussion they’re not really fully defined criteria, but gestures in the direction of whatever analogous criteria will make proper intrasystematic sense within a given worldview). To ask about the rationality of a worldview is to ask these kinds of questions.

If, however, we’re talking about the processes by which such a ‘worldview’ takes hold of someone, or lets them go, we might need another category. When someone slips away from Christian faith, for example, it seldom happens by means of one knockdown argument. Often it seems to involve a slow leeching away of that faith’s plausibility. ‘Plausibility’, here, is closely connected to the ‘habitability’ of that faith, – but now that habitability as compared to the habitability of other worldviews that are available to the person in question – other worldviews that he or she also partially inhabits. And this comparative habitability has to do with the ease, the facility, with which Christian ways of making sense come naturally and forcefully to hand as compared to some other way of making sense.

The leeching away of plausibility is the process by which this worldview shifts from being the water in which one swims to being a game that one plays, and from being a game that one plays to being a set of artificial moves that no longer form a whole – moves that sit oddly within some other context that has itself now usurped the aura of plausibility. In the other direction, a ‘worldview’ that ‘takes on the aura of plausibility’ will move from being a set of disruptive ideas, to being a game worth playing, to becoming invisible: the tacit rules that structure how one sees and moves.

Now, I live in a world in which Christian faith is counter-cultural (even though, in many contexts, ‘faithiness‘ is not). That is, I live in a world where what I am calling the Christian worldview tends only to flourish where people take pains over that flourishing, and where there is a background alternative worldview – in many ways inimical to Christianity – ready to take up the slack should faith weaken. Put it this way: I live in a world in which it is quite easy to stop participating in the eucharist, or reading the Bible, but rather more difficult to avoid shopping in supermarkets and watching Hollywood films. The disciplined practices that tend to sustain the Christian worldview are easier to avoid than the disciplined practices that tend to sustain one alternative.

Now: with that machinery in place, I can begin to approach my point. I spend a lot of my time skirting the edges of unbelief. For me, what I have been calling the ‘plausibility’ of Christianity ebbs and flows – and the sea of faith is not at high tide right now, and hasn’t been for a long time. In part, that has something to do with specific questions and problems that I have – specific matters of this worldview’s coherence and resilience. But only in part – and only in a pretty small part, if I’m honest. It is more a case of what I have been describing: the slow leeching away of plausibility. I spend quite a lot of my time at the ‘game that I play’ level of plausibility; on bad days I’m at the ‘set of artificial moves’ level. Only some of the time am I swimming in water that is truly transparent.

Now, an atheist observer might think that I simply lack courage to take the final step away from belief to unbelief – that I am held back by loyalty, by inertia, by fear, by cowardice. Come on, he might say, admit it: admit that faith has gone, and learn to celebrate that fact. (To be frank, though, it’s not so much Dawkins whose voice I hear at this point as Nietzsche, speaking in The Gay Science of the ‘freedom of the will [by which] the spirit would take leave of all faith and every wish for certainty, being practiced in maintaining himself on insubstantial ropes and possibilities and dancing even near abysses.)

That, however, is to beg the question. It is a description of my state (and a proposal of a solution) that only makes sense in terms of the atheist’s worldview – not in the Christian worldview. I cannot accept it as a reason for moving from the latter to the former without already having decided to move.

Instead, working still with the descriptions that make sense within Christianity (whether they come naturally to me, today, or seem artificial) I diagnose my plight differently. What do I expect, my faith tells me, in a life that sits so lightly to the disciplines that sustain faith’s plausibility? What do I expect in a life where the strings of prayer, of worship, of any form of devotion, are so very frayed? Any worldview (the atheist’s included) is sustained by disciplines of thought and practice; what do I expect from lack of discipline if not the leeching away of faith’s plausibility? Under such a description, the leeching away of plausibility does not tell me something uncomfortable about the Christian worldview, it tells me something uncomfortable about myself.

(Let me stress that I do not mean to suggest that doubt is sin. But some forms of doubt – if that is in any case a good word for this plausibility deficit – can be a symptom not of serious questioning and exploration, but of sloth: of having lazily allowed the fabric of faith to wear so thin that it frays.)

I do not mean this to be an ever-so-humble admission designed to place me in a good light, even though I know that there is no way of avoiding this being self-serving, no way of avoiding this itself being an appeal to you to marvel at my moral seriousness and clear-eyed self-scrutiny. I’m not talking about anything very interesting – nothing that involves any agonising or moral heroism or struggles at my personal Jabbok Ford. I’m talking about forgetfulness, about being bad at forming good habits, about boredom, about being easily distracted, about having will-power as strong as well-cooked spaghetti. It’s not going to make a good movie, believe me.

‘Sophisticated’ I may be, but I am not one of those in whom the Christian ‘worldview’ has remained second nature. I am not one of those who inhabits and embodies it deeply. And I am therefore – because these things do go together – not someone anyone should look to for the marks of those who do know this worldview more deeply: real discrimination, real judgment, real graciousness, facility and penetration.

I may be a good reader of texts on choreography, but you really wouldn’t want to see me dance.

So, ‘sophisticated’ I may be, but I think I count as one of Christianity’s ‘dim-witted’: those who labour to make out what others simply see; those who have to work at what for others has become second nature; those who know how to do this stuff in theory but fall over when doing it in practice. And I don’t think I can get away with some facile intellectual/practical distinction here, as if I’m good at the head stuff but bad at the body stuff. The facility, the grace, the judgment that those who more deeply inhabit the Christian worldview have – it’s a matter of what they see as much as a matter of what they do.

The real ‘sophisticates’ of Christianity are those who show Christian sophia: Christian wisdom. My sophistication is all second hand. I’m a a repairer of borrowed clothes

So, why don’t I leave the Church? Because these are my people: these are the anchors of my faith. Without them any version of Christianity that I tried to weave would be all thread and no fabric.

In the

In the  The sentence I have quoted comes after Dawkins’ discussion of the silliness beyond parody of Catholic beatification processes – a process that he assumes must be an embarrassment to ‘more sophisticated circles within the Church’. Then comes the line I started with: in context, a throwaway jibe. But although it is a throwaway line, a taunt rather than an argument, it echoes a more serious question that I have heard Dawkins ask, in his curiously engaging

The sentence I have quoted comes after Dawkins’ discussion of the silliness beyond parody of Catholic beatification processes – a process that he assumes must be an embarrassment to ‘more sophisticated circles within the Church’. Then comes the line I started with: in context, a throwaway jibe. But although it is a throwaway line, a taunt rather than an argument, it echoes a more serious question that I have heard Dawkins ask, in his curiously engaging  Anyone who has ended up reading this blog because of my

Anyone who has ended up reading this blog because of my

Recent Comments