The work in which the Church submits to this self-examination falls into three circles …

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics I/1, p.3

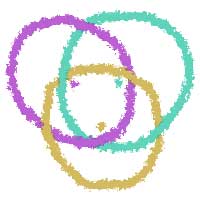

Prolegomena to theology normally explain the distinction and inter-relation of the various theological sub-disciplines. Barth offers a rather strange image of three overlapping circles, where the circles overlap so extensively that the centre of each circle lies within the overlap of all three.

The circles represent biblical, dogmatic and pastoral theology – covering, respectively, biblical exegesis examining the sources of the church’s speech about God, the coherent ordering of the content of the church’s speech about God, and some kind of reflection on the practical impact of the church’s speech. He explains that it is ‘as well neither to affirm nor to construct a systematic centre’ (4) governing all three.

The nature of the third of Barth’s circles (pastoral theology) isn’t very clear to me from what he says here – but I think I can grasp the general point by considering the relation of biblical and dogmatic theology.

Biblical theology is the discipline of examining the scriptures insofar as they are read by the church for the sake of their object, God’s revelation in Jesus Christ. It is governed by the order and flow of the texts that it reads, however much it includes abstractions and detours that step back from the text for some kind of overview – and its practitioners might rightly be rather suspicious of such overviews, to the extent that they lose touch with the cut and thrust of the text.

Dogmatic theology, on the other hand, treats the content of the church’s scripture-governed speech about God as a whole, and asks how the many claims involved are ordered – how what the church says in one place relates to what it says in another, what the limits are of its claims, and so on. It is governed by the way the topics of the church’s speech hang together – its ordering is conceptual – however much it might include detours and experiments that pursue the order of one of the biblical texts in play in a given question.

As such, biblical theology and dogmatic theology are disciplines with their own integrity. Within biblical theology, dogmatic theology must appear as an interruption, even a distraction – a useful and important abstraction, perhaps, but one that risks losing touch with the order of the scriptural texts. Within dogmatic theology, biblical theology must also appear as an interruption – a necessary and proper interruption, perhaps, but one that risks losing sight of the need to take responsibility for the church’s present speech about God as a whole, and attend to its interconnections.

There is no way of resolving this tension, because the object of theology is church practice insofar as it obeys scripture insofar as scripture speaks of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ. There is, therefore, an instability to theological practice – a lack of a systematic ordering that would make it clear which of the sub-disciplines properly governed the others. Rather, there is quite properly an ongoing process of mutual adjustment, of sometimes irascible conversation between the sub-disciplines. And this coheres with the idea that theology can’t guarantee its own success: there is nowhere to stand (no ‘systematic centre’) from which to declare that any settlement achieved between biblical and dogmatic theologians could not have been otherwise.

This post is part of a series on the opening of Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics I/1.

Recent Comments