Ch. 3: Arguments for God’s Existence

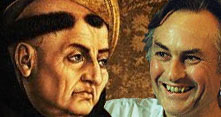

Dawkins’ misrepresentation of Anselm is as interesting as his misrepresentation of Aquinas. Here, too, I agree that Anselm’s argument does not provide a successful proof of the existence of God (in the sense that Dawkins is discussing), so it’s not that I disagree with Dawkins’ conclusion. Nevertheless, his way of arriving at that conclusion is instructive.

Dawkins’ misrepresentation of Anselm is as interesting as his misrepresentation of Aquinas. Here, too, I agree that Anselm’s argument does not provide a successful proof of the existence of God (in the sense that Dawkins is discussing), so it’s not that I disagree with Dawkins’ conclusion. Nevertheless, his way of arriving at that conclusion is instructive.

Let’s get the uninteresting aspects out of the way first. Dawkins’ primary weapon is ridicule. He explains the argument in such a way that it is impossible to see how anyone could be convinced by it for a moment. He then notes that Bertrand Russell said both that it is quite difficult to work out why the argument does not work, and that he himself, in 1894, had become convinced that the argument did in fact work – though Dawkins has already made it impossible for us to see how either of these claims could be true. He is tempted to attribute the latter, in particular, to Russell being exaggeratedly fair-minded, over eager to find worth in something clearly worthless. I rather suspect that, if the quotes form Russell show us anything, they show us that the argument must be more interesting, and more complex, than Dawkins’ ridiculing summary suggests: Dawkins has again substituted derision for argument.

However, he is quite explicit about his reason for this, and that’s where the more interesting aspect of his account lies. He makes it clear that, as a scientist rather than a philosopher, he simply can’t begin to imagine that an argument that draws on no empirical data- that deals simply in words, in logic – could prove something factual about the universe. And that, I think, confirms the impression I was left with by his treatment of Aquinas: that, for Dawkins, the question of the existence of God is the question of the existence of some particular thing – one thing amongst all the things that exist: some kind of empirical reality. He is understandable unwilling to believe that a purely philosophical argument could establish, without any kind of looking the existence of such a thing.

What if, however, the question of the existence of God were more like a question about the conditions for the existence of all particular things? Would it be more plausible to think that a philosophical/metaphysical argument might be capable of establishing the necessity of something more like that? Some people have thought, for instance, that it is possible to prove philosophically that the universe could not be infinitely old; I happen to disagree, but it is, I think, easier to see why someone might think that something like that might be susceptible of purely philosophical proof, than why someone might think that the existence of the planet Jupiter might be susceptible of such a proof. What if the God that Anselm and Aquinas talk about is not best understood as a particular thing, a specific empirical reality, and instead is something that in some respects is more like a basic condition for all particular things?

Note that I am not saying that I think Anselm’s argument works – at least, not if we take it as a proof of the existence of God in the sense we’re discussing. But might it be possible down this route to see why it is interesting, and why versions of it have (however briefly) convinced people as brilliant as Russell?

Once again, we come down to differing understandings of the word ‘God’ – and to the inadequacy of Dawkins’ version of ‘supernaturalism’ to cover some of the things that ‘God’ has meant.

Just in case you can’t be bothered to work through my

Just in case you can’t be bothered to work through my

Recent Comments